I was fourteen years old when a man grabbed me by the pussy.

We were in the checkout line of our Pacific Northwest town’s Payless drugstore. It was early evening, one week before Valentine’s Day, and I was buying a cassette tape as a gift for my best friend. (The Thelma & Louise soundtrack. Seriously.) My parents were waiting in the car. I’d stepped up to the cashier when a hand squeezed my ass.

I was not raised to fight for myself or others. My family consisted of three isolated people who neatly sidestepped not only conflict but engagement of any kind. I knew neither fight nor flight; I knew only to cringe into my body like a potato bug. To make myself disappear.

The man circled me. He cupped the front of my jeans, slid his fingers against my vulva, and squeezed. We were alone in the checkout lines – alone with the two women working the cash registers, alone with my frozen feet and pounding heart. No one spoke. I remained paralyzed. He released his hold on his own time, sauntering out of the store on his own terms. Change broke the silence. Coins clattered against the counter as I paid for the tape, never making eye contact with the cashier. I forced numb legs to step through the sliding doors, into the darkness where he might be waiting, and slid silently into the backseat of the Datsun. I didn’t say anything to my parents.

At fourteen, my ugly duckling childhood was barely a year behind me. The transition happened so unexpectedly and without warning, I didn’t yet understand the distinction between attraction and abuse. I didn’t understand unwanted advances weren’t about me, but power and predation – the flexing of rape culture’s muscle. I thought it was my fault that grown men suddenly evaluated me in a way they hadn’t before, openly, as their right. Some I’d known as family friends: the elder fisherman having coffee with my mom on our boat, who, when I described having “worked my ass off,” was quick to correct me, “It’s still there – I noticed!” Others, like the man in the drugstore, were strangers.

Several weeks later, my mom reeled back when I came downstairs one morning. “What happened to you?” she gasped, grabbing my chin and forcing my face up. “Who did this to you?”

I didn’t want to tell her. To acknowledge the long red wounds where I’d dug my fingernails into flesh and pulled, as if in opening skin I could open a door to step back in time, back to a time when I hadn’t felt men’s roaming eyes and hands… That was an exchange too intimate for our family. But she persisted. Finally I confessed, “I didn’t want to be pretty anymore.”

Twenty-five years later, I still see her face crumpling, falling under the weight of grief she didn’t have words for, outrage she’d never been allowed to express.

My mom.

My mom and I exist at arm’s length. We subsist on three-minute phone calls and occasional visits where stilted conversation clings to such banal topics as the weather and her friends’ health woes. Avoidance of anything more substantial is by mutual, unspoken agreement. I broke that agreement only once, when, exasperated, I named the tension between us, saying the time we spent together couldn’t be fun for her.

“This is fun for me,” she insisted. She just wanted to show me her gardens and have tea together, she said. “I’m not going to talk to you about politics or sex or religion! You don’t have any idea who I am.”

She wasn’t wrong. But she wasn’t entirely right, either. I know pieces of my mom, pieces I carry like coins in my pocket.

Born in 1942, she was her parents’ first child. When her brother was born four years later, her mother told her how relieved she was to have had a son. Boys were better than girls, she explained.

While all boys were better than any girl, my mom learned over the course of her childhood that individual girls merited varying degrees of value. She learned that she, a studious, quiet type, was the wrong kind of girl. Her mother told her so, wondering aloud why she couldn’t be more like the pretty, vivacious girl next door.

My mom didn’t pass that cruel measuring stick on to her only child. Instead my inheritance consists of stories and observations jangling against each other. She was one of three women in her veterinary program at Cornell University. One of few female skippers in Southeast Alaska’s commercial salmon fishery, and the only one with a teenaged daughter as her crew. She spent her sixties as the only woman on her team at an oil refinery. Though she refused to apply a feminist frame to her achievements, that was how I viewed her. My pockets sag with gold, a coin for every powerful memory.

They aren’t all gold. Other memories are pennies, pitted and green with corrosion.

One. We stand side-by-side, inspecting make-up in a drugstore. It’s the same Payless that will soon teach me the dangers of my femaleness, but today’s only lesson is a 50-year old woman turning to her 13-year old daughter, asking if a particular shade of eye shadow will help her look pretty.

Two. I am working at a truck shop across from her house. I am the only female on the shop floor, other than those spread-eagled across the walls. When I come home broken from a particularly hard day – when the n‑word is used to describe Dr. King; when a staff meeting includes blasting a left-leaning local woman as an anti-war cunt; when my boss gestures to one of the posters and says he’d like to see me in that little black number – she waves a hand in discomfiture. “Oh, well…” She changes the subject.

Three. I perch on the edge of a chair at her dining room table. She’s urged me to come for dinner – “Won’t that be fun?” I’m watching her offer to cut a man’s steak. He’s had a seat at her table for the past twenty years, whenever the mood suits him, and is accustomed to being the center of her attention. Tonight he makes loud observations about the slice of cake on her plate and which parts of her body the calories will settle upon. I counter that she’s an adult and can eat whatever she chooses, but the defense is lost beneath the sound of my mom laughing at his “joke,” the sound of my mom agreeing, “I know, Bud, you’re right.”

Four, five, six. I watch my first and most defining female role model, the most capable and strongest woman I’ve known, bow to men unworthy of her, unavailable and withholding. I watch her opinions take on the shape of those of the men around her. I watch her make pieces of herself disappear.

This September, I returned from five months at sea. My mom was eager for me to visit, to see the improvements she’d made around her place. “I think you’ll be really pleased!” She yearns for my approval. In this way, I have been no better than the men she’s surrounded herself with: unable or unwilling to give what she seeks.

Driving into her rural neighborhood, I wasn’t surprised to see my old employer had erected a Trump sign in front of the truck shop, just rolled my eyes. But the mirror image reflected across the street stunned me. I’d never known my mom to reveal her political preferences; she avoids at all cost conversation that might be controversial.

Staring at the sign jabbed in my mom’s yard, I felt the way I imagine she once did, seeing her fourteen-year old daughter’s self-hate etched into her skin. Horrified, helpless. Heartbroken. Both of us so far beyond each other’s reach.

What happened to you? Who did this to you?

If I could, this is what I would do. I would pull out my pockets, gather those gold coins and melt them down. One woman’s value: absolute, unmistakable. I’d draw back a fist to hurl the corroded pennies away – down a wishing well, maybe, drowning those images of subjugation – but would stay my hand at the last second, understanding just in time that pain is its own kind of protection. Into the flames the pennies would go.

After the smoke cleared, I’d place a breathtaking swirl of metal, a shield of unique sturdiness and heft, into my mom’s hands. No one would ever reduce it to “pretty.” With that shield I would give her anger and grief, the certainty to refute anyone’s assessments of her body, her mind, her self-worth. I’d give her emotions we have never known how to exchange – confidence, joy. Trust. I would pass on to her every survival tool she wasn’t able to give me. I’d give her everything she never received herself.

But that’s a kind of change I don’t know how to make.

So I draw upon what I have: my vote. I vote as if my ballot might take back every time we laughed at our own expense, held ourselves responsible for a man’s behavior, blamed our bodies as the offender, changed the subject rather than the narrative. Every time we made ourselves small. My mom and I may never learn how to be whole and visible to each other. Still, even if we just cancel each other out, I vote as if we might yet share a safer, more equitable world.

[Gratitude to Dawn Quyle Landau for originally publishing this essay as a guest post on her blog, Tales From the Motherland, on November 6, 2016. It bears re-posting here, today, as an oath to refuse to normalize what is decidedly not. I’ll see you in the streets tomorrow, dear ones, and over the days to follow. May we resist and rise together.)

Thank you very much for your eloquent voice. I took your recommendation at the end and posted it on my own feed on Facebook.

Rick

Rockport, WA

You have written a very powerful piece Tele. Mu wife and I have watched what has unfolded south of the border and cannot imagine how it would feel to a caring, thoughtful, committed person living in the US. Most of us Canadians think as social democrats; even conservative leaning people. We have socialized medical care, welfare systems, that are not perfect, but do act as a safety net, and I think a basic Canadianism; that Canadians care about other Canadians. We are a country of Communists to Republicans. What happens there will affect us here, but our avenues of protest will be limited. We will truly return to the situation of the mouse that fears the elephant’s sneeze. What is most stunning is that the folks that will lose the most, and be hurt the most in the US, were those that opened the door to this Lewis Carrols Madhatters Tea Party. And the other thing that is very distressing to us, is that the legacy of Barack Obama will be eradicated as efficiently as in a Soviet Progrom. Not everything he did was right; but a lot of it was, considering the Republican Congress & Senate spent all their time trying to foil and discredit him.

Tele, your passion, and your writing, will have to be one of drops of rain that becomes the torrent of vigilance and scrutiny to limit the destruction of the rights of the citizens of your Republic. We all need good luck over the next four years.

So sad for the abuse you experienced becoming an adult. Totally raw and honest.

I especially identified with the story of the difficulty communing (and communicating) with your mom. I keep thinking if I was physically closer to my daugther or exposed more frequently we would relate more easily…maybe — maybe not. I share your pain (in reverse).

Tele, you are a phenomenal writer! Thank you so very much for putting words to our history, thoughts and emotions. You and your experiences are not alone.

We stand with you and know the next few years we will have to defend our freedom.

Please be our voice and I, for one, will march with you!

Tele, hi.

How propitious to hear (read) your strong voice during this nauseating transition. I’ve dropped off social media the last few years as it seemed to be more of a time suck. But it was a pleasure watching your star rise and your followers grow, until I felt there was really nothing I could add.

My brother, the commercial fisherman, is retiring – selling his boat and moving to New Zealand – for at least six months of the year. It might be a plan, considering the times we live in.

My surrogate mom, and best friend for a quarter century, passed away just before Christmas. My own mother disowned me the minute I turned eighteen, as no longer her pecuniary responsibility, or kin. I expect we all have our “mother” stories.

Maybe I’ll be able to catch one of your appearances in Oregon, where both of my sons now live. Would love to see you in person. In my heart of hearts you are like the daughter I never had.

Keep up the great work, as I know you will.

Wow Tele.

If the purpose of art is to disturb you have done your job.

I look forward to seeing and hearing you in Astoria.

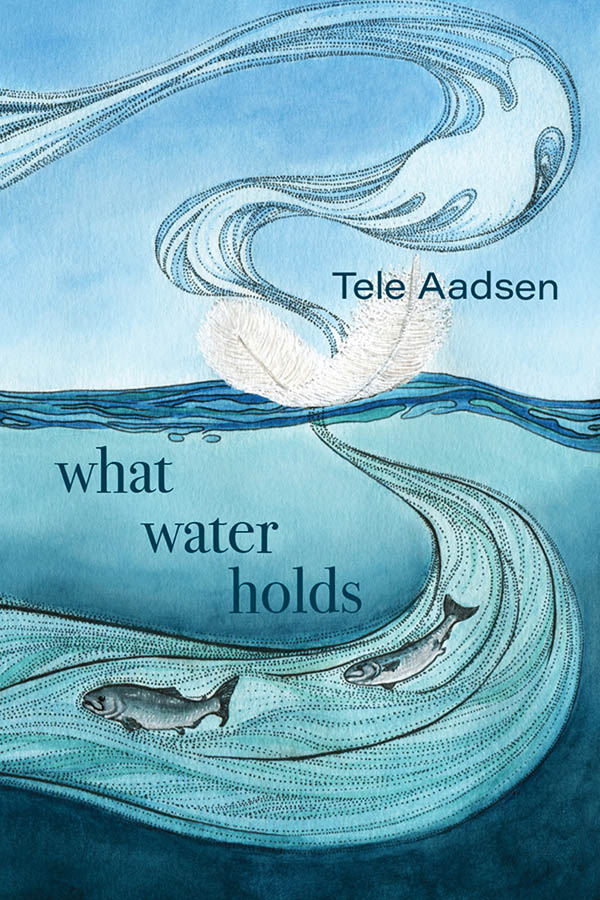

What is happening with the publication of your book?

Thank you Tele — for this piece, and for doing the work of revealing, of untangling and cutting ties with patterns that were increasingly toxic or painful the farther you go back in history. Carrying transgenerational wounding is something we all do and bear, and we all have the choice whether to repeat our past or re-author the narrative for ourselves and those who come after us.

I appreciate the love and courage it takes to write about family members in this open and vulnerable way, holding compassion and love and a wish for what you’d want your mother to have and be, and an acknowledgement of what was and still is a challenging relationship.

Looking forward to seeing you at FisherPoets in a couple short weeks.

I am ever moved by your honesty. Your guts. Your willingness to take a stand fully exposed. Thank you for writing this, Tele.

Thank you, Tele! Your post helps me to answer when I question myself.

I just had a firm talk with an officer who decided that a verbally abusive man using his rambunctious dog as an aggressive extension of himself is not a threat to a woman. No, not a problem at all, because the woman, me, spoke back. “Words were exchanged,” the officer said. As if I should not respond to the large dog running at me, jumping on me, the man yelling “Shut up!” and “Fuck you, Bitch.” The officer supports the abusive man, encouraging him, as the current political climate encourages him, to be an abuser.

A woman, with no “authorities” to turn to, has to be her own authority.

My mother, also a strong career woman, nonetheless expected me to be subservient to a husband no matter that he harmed me. My daughter is stronger, and I revel in her ability to be smarter than my example at times.

Tele, your writing is beautiful, and it has helped me.

Jo, thank YOU. I’m only just now seeing your comment, and appreciate you speaking up — then, with the officer & dog owner, and here, in your comment. Thank you for your kind words. It’s mutual: your comment (“A woman, with no ‘authorities’ to turn to, has to be her own authority”) will be ringing in my ears for a long, long time, and that will help me.